Debates

HowTheLightGetsIn London 2019 featured over 70 debates and talks with the world's leading thinkers on everything from post-truth and paradox to artificial intelligence and adventures in space. Get to know the big ideas below.

HowTheLightGetsIn London 2019 featured over 70 debates and talks with the world's leading thinkers on everything from post-truth and paradox to artificial intelligence and adventures in space. Get to know the big ideas below.

Bad Boys

Bad Boys

It used to be an uncontroversial statement: bad boys are sexy. From iconic actors like James Dean and Johnny Depp to fictional characters like James Bond and Indiana Jones, the silver screen served us up the men our mothers warned us about. But now, traditional masculine qualities are being called out as toxic, and many wish to cleanse the world of the men we love to hate.

Should we celebrate the opportunity to redefine masculinity, replacing bad boys with more positive role models? And if so, what does that new masculinity look like - and does it still have sex appeal? Or do we need to admit that danger is integral to desire, and see the attempt to cleanse masculinity of all its vices as a mistake that will leave everyone worse off?

Editor of The Amorist and Telegraph columnist Rowan Pelling, author of What Women Want Ella Whelan, and broadcaster Myriam François imagine a new masculinity.

Victims and Warriors

Victims and Warriors

Once it was seen as a personal quality to battle through troubles without complaint. Now it is more likely to be seen as lack of human emotion. Moreover, drawing attention to misfortune and adversity, as identity politics testifies, has become a powerful political force.

Should we encourage this abandonment of the hierarchical stiff upper lip culture that once embedded privilege and power, and welcome a necessary shift towards hearing and supporting the vulnerable? Or should we be wary of a focus on weakness and victimhood, which risks undermining the individuals involved and damaging social cohesion?

Human rights and LGBT+ Campaigner Peter Tatchell, journalist and founder of MsAfropolitan Minna Salami and Times columnist David Aaronovitch debate the best route to empowerment.

Masters of the Universe

Masters of the Universe

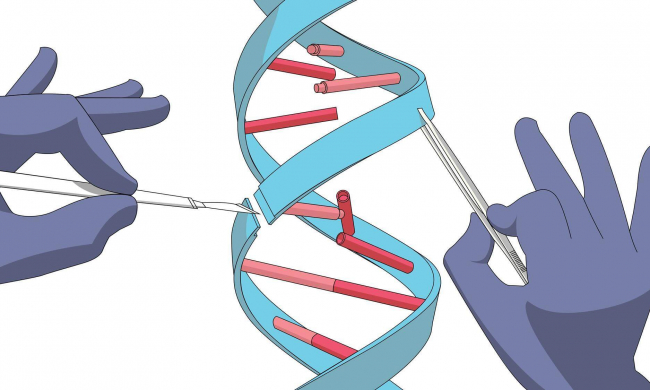

Ever since the discovery of DNA, we have fanstasised about creating new species of animals, or even 'improved' humans. But it is only in the last few years that a new gene editing technology, CRISPR, has made this a reality. Many claim it is already unstoppable, that we will always demand solutions to diseases if they are possible. Is CRISPR the key to improving health and defeating ageing? Will it lead to a new age of transhumans and unleash humanity's potential? Or is this a dangerous fantasy that could lead to the reckless use of a technology we need to limit in order to safeguard the human race?

Author of Superior Angela Saini, molecular biologist and Director of Editing Nature at Yale Natalie Kofler and founder of Humanity+ David Pearce explore the radical new possibilities of biotechnology.

Into The Unknown

Into The Unknown

Fifty years ago we landed on the moon and imagined that in 2001 we would be travelling vast distances through space. But the fantasy died and we went nowhere. Now a new age of space exploration is underway - this one driven by companies, billionaires and new players like China and India.

Is it an essential trait of being human to reach out into the unknown? Should we applaud a return to grand adventures with the potential to replenish the planet's depleted resources from the Moon, Mars and beyond? Or should we give up on our Space Odysseys and recognise that the scale of space leave us trapped amid the barren planets of our own solar system?

Astronomer Royal Martin Rees, philosopher and author of Nobody Owns the Moon Tony Milligan and Senior Strategist for Airbus Elizabeth Seward reach out to the cosmos.

In partnership with Airbus

Modern Crises and Ancient Gods

Modern Crises and Ancient Gods

For much of human history nature was our god. We worshipped the sun, the moon, or in Northern Europe the tree gods. Human gods followed. And then science arrived and seemed to sweep them all away. Yet now science and technology which once tamed nature is seen by many as plundering the planet and wrecking the climate. And the Gaia gods are back in fashion.

Were the ancients right, and nature the source of all things and that which we should guard most closely? Should we build a whole way of life, even a theology, with nature at its heart, and might such a radical change be the only way to save us? Or is this a backward step, superstitious and dangerous, and instead renew our belief in progress and human ingenuity to solve our current problems?

Former leader of the Green Party Natalie Bennett, former Chief Scientific Advisor David King and European Director of Brahma Kumaris Sister Jayanti reimagine our place on the planet.

Satisfaction and Desire

Satisfaction and Desire

150 years ago life was short and luxuries scarce. By comparison ours is a largely affluent society and most have plenty. Working class Victorian women usually had one dress. Today, we have so many clothes that on average 77% of our wardrobe is not worn in any one year and half are never worn. Yet many of us remain unsatisfied and spend our lives feeling unfulfilled and chasing ever more.

Is discontent with our circumstances both universal and natural, making never being satisfied an inescapable part of being human and a vital part of our success? Or is our dissatisfaction a form of greed encouraged by a relentlessly material culture that is not good for our own well being or the planet - and should we as a result engage in a radical overhaul in our goals and values?

Economist and author of The Value of Everything Mariana Mazzucato, Director General of the Institute of Economic Affairs Mark Littlewood and author of Plunder of The Commons Guy Standing clash over our wants and needs.

In association with The Observer

Virtue and Vice

Virtue and Vice

Many would argue that for at least a century we have been moving away from the moral certainties of traditional Christianity. Yet now a new form of moral certainty is reappearing, with much of our culture seemingly gripped by a focus on virtue and a tightly policed sense of right and wrong.

Should we welcome this return to virtue and embrace a new moralism that will purge society of its newly found sins? Or are these new certainties new prejudice and the intolerant assertion of tribal attachments? Is our culture morally bankrupt in need of greater virture, or could we be in the early stages of a Salem witch trial?

Chief Executive of The RSA and former head of the No. 10 Policy Unit Matthew Taylor, ethicist Rebecca Roache and philosopher and Closure theorist Hilary Lawson make their case for the future of morality.

In association with Aeon

In Search of Freedom

In Search of Freedom

Once it was straight-forward. We were born free and shackled by self-serving authority. Now many, from neuroscientists to social theorists, argue we are not free in the first place. Constrained by our genes, manipulated by technology and the cultural zeitgeist, there seems little space left for individual freedom.

Should we conclude that the very idea of freedom was a mistake? Or is this a madness that threatens our personal lives and the culture on which the West was built?

Historian of ideas and author of Life Lessons from Hobbes Hannah Dawson, post-realist philosopher Hilary Lawson, neuropsychologist and science writer Paul Broks and author of Freedom Regained Julian Baggini ask who's really in control.

Popularity and Prejudice

Popularity and Prejudice

There has always been dispute over which ideas are most significant. But there used to be broad agreement about the qualities required and the great works of the field. Now from the creative arts to the social sciences there are claims that previous standards were forms of prejudice and calls are heard for greater inclusion.

How do we navigate this new space where there is no agreement on merit? Should the origin of an idea be as important as its content? Should we abandon the idea of great works altogether? Or does this threaten the very success of our culture and all that we hold to be valuable?

Founder of MsAfropolitan Minna Salami and literary theorist Stanley Fish rethink what makes a great work of art.

Metropolis Untamed

Metropolis Untamed

The digital and tech giants began with cuddly logos and hip slogans but they are rapidly turning into a 21st century version of Fritz Lang's 'Metropolis' as with breakneck speed they turn into the largest corporations the world has ever seen. (Apple alone is worth more than the GDP of 90% of the countries in the world). Many now see them as malevolent monopolies, with massive largely untaxed profits that manipulate our behaviour for their own benefit. Some even claim the epidemic of mental ill health can be laid at their door.

If we decide we want to escape from their vision of the future, is there anything we can do to stop them? Does their power and influence signal the loss of control of national governments to global corporations? Or are the fears overdone and is it still possible for governments to fight back? And if so how?

Author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism Shoshana Zuboff, Conservative MP Bim Afolami, author of Zed, Joanna Kavenna, and Labour MP Angela Eagle debate the power and peril of the tech giants.

In association with Prospect

What's Wrong With Us?

What's Wrong With Us?

Human mortality has meant that we have often revered doctors even when historically their remedies and cures were unfounded. Little it seems changes. In a recent US study doctors were only accurate in 55% of easy cases and just 6% of the time in difficult ones. But now computers have the potential, and some claim are already able, to aggregate across all human conditions and analyze symptoms to determine what is wrong with us more accurately than ever before.

Will this make doctors redundant? Will it usher in an era of diagnosis that is hugely superior to current human judgments? Or is there something special about human analysis which computers can never match?

Palliative care doctorand author of Your Life in My Hands Rachel Clarke, psychiatrist David Healy and Oxford University futurist Anders Sandberg ask whether AI might one day keep the doctor away.

The Future of Thought

The Future of Thought

China's economic rise has been both meteoric and relentless. Few now doubt that it will shortly eclipse the US and become the largest economy in the world. But we still tend to imagine that Western ideas will continue to dominate.

Is this an illusion? Contemporary Chinese thinkers argue that ancient ideas such as Tianxia have greater potential for global harmony than western ideas of individualism. Is the sun setting on Western ideas as well as Western economies? Or is Western thought essential to growth and progress -and already embedded in China's success?

Author of How the World Thinks Julian Baggini, political philosopher Jamie Whyte and Oxford Professor of China Studies Vivienne Shue consider China's influence on the future of ideas.

In association with Prospect

A Crack in Everything

A Crack in Everything

Once we assumed that reason and rationality would gradually uncover the truth. But from quantum mechanics to set theory, positivism to deconstruction, philosophical realism to philosophical relativism, paradox it seems is found at the heart of our most revered theories and at the cornerstones of our thought.

Are these paradoxes evidence that our theories are wrong and is it essential that they are overcome? Will we one day find our way out of the hall of mirrors if we reason hard enough? Or should we accept that paradox is an unavoidable consequence of human thought, and a hint of the greater world that lies beyond the limitations of human understanding.

Live from Ljubljana, philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek joins Oxford and Keele metaphysician Sophie Allen and post-realist philosopher and author of Reflexivity: the postmodern predicament Hilary Lawson to ask why paradox just won't go away.

In association with Aeon

Lies, Damned Lies, and Post Truth

Lies, Damned Lies, and Post Truth

It seemed that we had got used to the idea that rather than a single definitive truth there are a multiplicity of competing and alternative perspectives. But with the rise of 'fake news' and the publicising of blatant lies, many want to reassert the importance of accuracy and truth.

Can we call out lies and deception while still allowing for radically different ways of seeing? Is there a difference between truth within a perspective and truth that extends to all perspectives? Or should we simply conclude that postmodernism and relativism were a dangerous mistake?

Author of Post Truth Steve Fuller, theoretical philosopher Åsa Wikforss, continental philosopher Sacha Golob and former Moscow journalist and author of This is Not Propaganda Peter Pomerantsev ask whether anybody has a monopoly on truth.

Education has long been seen as the primary route to personal and social progress. But critics now argue that the encouragement of ever more education for a longer period in subjects largely irrelevant to working life is mistaken. Some go further claiming that post-graduate degrees are little more than pyramid schemes, driving university income but of little or no value to the individual or society.

In the age of Wikipedia should we give up amassing knowledge as a measure of success, and seek to acquire judgment rather than knowledge? Do we need a radical re-think of our educational goals and how they should be delivered? Or are our current universities a great institution and a global UK success story?

Blair's Education Minister and Labour Peer Andrew Adonis, former leader of the Green Party Natalie Bennett and libertarian economist Jamie Whyte consider a crisis in higher education.

The End of Left and Right

The End of Left and Right

Since the French revolution we have divided politics into left and right and our political parties with it. But increasingly these categories are challenged, and as Brexit made clear, the opposition is not always relevant or helpful. Is it time to move on? Are left and right the antiquated legacy of an era no longer relevant? Are there alternatives that would be better descriptions of our current politics, or which might help us improve and transform political debate? Or does the distinction between the progressive left and the conservative right remain the central issue of our time?

Author of The Road to Somewhere David Goodhart, Conservative leadership candidate Rory Stewart and political theorist and author of For a Left Populism Chantal Mouffe debate new political divides.

The Making of Us

The Making of Us

Most of us believe that our upbringing and our environment are critical to our success and to shaping the person we become. Yet a flurry of books from behavioural geneticists backed by long term twin studies contend that our DNA is primarily responsible for determining who we are.

Is genetics more influential than we have come to imagine? Are parents deluded when they imagine the upbringing and schooling of their children is vital to their future? Or are the studies and the apparent evidence dangerously misleading and socially regressive, cementing privilege for those with privileged backgrounds and undermining adversity and disadvantage?

Author of Blueprint Robert Plomin, geneticist at The Francis Crick Institute Güneş Taylor, author of The Essential Difference Simon Baron-Cohen and author of Superior Angela Saini lock horns.

The Malthusian Catastrophe

The Malthusian Catastrophe

Many see overpopulation as the greatest threat of our timeand even figures like prince Harry have argued for limiting their numbers of children as a result. Yet Japan and Russia already have declining populations, and some predict China's too will soon plunge. Peak children has already arrived. Might Elon Musk be right that the real threat is not population growth, but rather a collapsing global population, with untold consequences for prosperity and human development? Or with nearly 8 billion humans on the planet is a radical reduction in numbers the only sustainable solution?

Author of On the Future Martin Rees, author of The Human Tide, Paul Morland and former leader of the Green Party Natalie Bennett debate debate the perils of population.

It’s been 150 years since Matthew Arnold wrote of the "melancholy, long withdrawing roar" of faith in God. Yet as our churches have emptied, our belief in progress, science and reason has also begun to falter, and we find ourselves in a new space in which all beliefs are challenged, and perspectives jostle in a relative world.

Finding ourselves lost, should we look once more to the spiritual realm to make sense of our limitations? Might religion, in the form of shared rituals and values, once again have a role to play? Or are religions anachronistic, often dangerous, belief systems that should be consigned to the dustbin of history?

Research associate at the Centre for Islamic Studies at SOAS Myriam François, Oxford scientist and humanist Peter Atkins and philosopher and Closure theorist Hilary Lawson debate spirituality and secularism.

Seeing How It Is

Seeing How It Is

From Newton to Darwin, Curie to Einstein, science has been built on empirical observation. And today, we rely on Big Data technology to analyse huge amounts of data - from ocean currents and the climate to changing populations.

It seems we know more than ever about the world. But at the same time the very idea of neutral observation is under threat. In a postmodern world many argue that all observation is from a perspective, everything we see influenced by what we already think.

Are we at sea in a world of competing models? Or is it time to reassert the value of empirical observation, supported perhaps by machine learning and big data, as a means of choosing between incompatible theories?

Author of The Science Delusion Rupert Sheldrake, sociologist of science Steve Fuller, eminent Oxford chemist Peter Atkins and author of Superior Angela Saini test out the foundations of science.

For al long time Britain has been politically stable. Chaotic government, revolutions and civil war were the wild actions of other nations, but not us. Yet now our society is fiercely divided, each tribe rigidly certain of their moral rectitude, unwilling to negotiate or even converse with their adversaries. And with the yellow vests bringing violence to the streets of Paris earlier in the year it is not only Britain that seems to be edging towards instability.

How does a culture rediscover harmony when it is deeply divided? Is it possible that the UK could be closer to large scale social unrest than we imagine? Have toleration and pluralism run their course? Can we forge a harmonious future, or are peace and stability necessary casualties when there is so much at stake?

Founder of Novara Media Aaron Bastani, former leader of the Liberal Democrats Vince Cable, and political commentator and journalist Ella Whelan consider the conflict to come.

The Mystery of LIfe

The Mystery of LIfe

Life is strangely puzzling. Genetics and evolution have combined to give us a seemingly detailed account of life on earth. But science remains uncertain, and theories abound, about just how it began. We don't even have an agreed definition of what life is.

As we explore the planets of the solar system researchers hope they will find evidence of life. But would it be like life on earth? Would we be able to identify it as life at all? Or is the wish to find other life forms a science fiction fantasy that serves Hollywood well but has little to do with reality?

Biochemist and author of The Vital Question Nick Lane, Head of Future Missions at Airbus Ralph Cordey and leading British space scientist Monica Grady grapple with the mysterious puzzles of life.

In partnership with Airbus

When The Empire Falls

When The Empire Falls

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States became the sole superpower and global policeman. Now China is challenging the US in Africa and Southeast Asia, Putin has outmanoeuvred the West in Syria, and Trump has confirmed the new global state of affairs by calling for an end to the Pax Americana.

Historians argue the end of the Pax Britannica after World War I led to the rise of Hitler. Will the end of Pax Americana be equally catastrophic? Do we need new alliances, and new arsenals, to avoid future conflagration? Or is there little to fear and should we see such scenarios as exaggerated and overblown?

Director of the IEA, Mark Littlewood, Former Secretary of State for International Development, Clare Short and British political activist, Tariq Ali.

The One True Story

The One True Story

From Plato to Aristotle, Russell to Wittgenstein, we traditionally see philosophers as engaged in the disinterested pursuit of truth - a view philosophers themselves are inclined to encourage. But in a postmodern world, shaped by Richard Rorty's claim that philosophy is merely a form of 'cultural politics', few now imagine that truth with a capital 'T' can be uncovered.

Must we abandon the ideal of a philosophy devoid of motives and social goals? If so, how is such a philosophy to be distinguished from literature, or politics? Should we hold on to philosophy as the pursuit of the one true story of the world, with logic and rationality central to the endeavour, are these themselves rhetorical tools to convince the unwary?

Novelist and former UN conflict advisor Janne Teller, director of the Institute of Philosophy Barry C. Smith and philosopher of metaphysics Silvia Jonas take truth and neutrality to task.

Reigning Men

Reigning Men

Fourth wave feminism and the #MeToo movement looked as though they were going to change the world. But with Trump tipped by many to win a second term and Johnson selected from an all-male shortlist, it seems that reality may be more complex. Women run just 20% of the UK's businesses and female entrepreneurs receive less than 5% of venture capital funds.

Is the continued dominance of men in many fields a sign that ingrained prejudice is profoundly entrenched? If so, how can it be overturned? Is it just a matter of time before things even out, or are we mistaken to look for equality in every sphere and instead seek to increase the value of roles in which women already excel?

Journalist and visiting Fellow of All Souls, Oxford Mary Ann Sieghart, author of One Dimensional Women Nina Power, and lecturer and author of Becoming Beauvoir, Kate Kirkpatrick ask whether the sun is setting on the reign of men.

Is Capitalism Broken?

Is Capitalism Broken?

It is just twenty-five years since Fukuyama's claim, taken seriously at the time, that capitalism and liberal democracy had won, and represented the endpoint of cultural advance. Instead, after a decade of stagnation marked by extremes of wealth and opportunity, it seems that capitalism, far from being victorious, is fundamentally broken.

Is capitalism in need of reform, or is a more profound change required to create a fairer and more equal society? Or, despite its flaws, is capitalism still the only reliable driver of improved living standards from London to Beijing?

Author of Plunder of The Commons, Guy Standing, politician and libertarian economist Jamie Whyte, FT Alphaville editor, Izabella Kaminska and senior economic adviser at HSBC Holdings, Stephen King ask whether we can save Capitalism - and whether we should.

From the aristocrats who awaited Mozart's latest compositions to the pop charts of today, from our desire for the latest fashion to our focus on the latest film or book, the new has driven music and culture for hundreds of years. But that was in an era where access to art was limited. Now we potentially have access to everything. Music from every culture and era, every style, every film, every book.

In this unparalleled space, should we escape the tyranny of the new and seek out the best from the unknown and uncelebrated, from distant lands and other times? Is art not about the novel but about lasting value? Or is the new, though limited by place and time, necessarily more vital than past?

Composer and former musical director at Shakespeare's Globe Claire van Kampen, film director Sophie Fiennes, Observer music journalist Ammar Kalia and art rock icon Brian Eno debate the value of the new.

In association with The Observer

A Truly Unique Offering

The Independent

Press